Not all the so-called Chinese railroad workers who helped built the US railways were actually Chinese. Some weren’t even ethnically Chinese. That’s a different kind of erasure that I began wondering about after I saw the film “Train Dreams” and read the novella. The dates troubled me, but my knowledge of Idaho history was limited and I learned that my knowledge of Asian American history was also limited.

Japanese Immigrants and the Railroad

When I was a child, my mother told me that my grandfather had worked on the railways. I thought she was mistaken and my grandfathers have both died before I was born. Even when I was in high school, I never read about Japanese immigrants working on the railways. That came so much later that I thought my mother had been mistaken. Even when I found out Japanese worked the railways, I thought it was limited to California.

But the Japanese railway workers went beyond the borders of California.

Labor agents, or “bosses” made arrangements to find jobs, housing, food and clothing for these men in exchange for a fee and percentage of their earned wages. After working on a section gang himself, Edward Daigoro Hashimoto found his way to Salt Lake City and established the E. D. Hashimoto Company in 1902. Nicknamed “The Mikado”, he furnished section gangs for the Western Pacific and Denver Rio Grande Railroads, along with miners for Bingham and Carbon County. By 1906, over 13,000 Japanese immigrants worked for the railroads. A few years later, at the urging of anti-Asian groups in the west, Japan was pressured and agreed to stop labor immigration to the United States under the Gentleman’s Agreement of 1908. Working on the section gangs was a harsh life, especially for those who now had families. Once they settled into communities, many left their jobs at the railroad to work at other trades such as farming or saved up enough money to start businesses of their own. Japantowns began to emerge in cities like Ogden and Salt Lake City where railroad stations were located.

The Japanese laborers also worked in Wyoming.

As early as 1902, shortly after their introduction to Wyoming, the Union Pacific promoted Japanese men to track foremen. This was partly out of necessity because of the diminishing supply of workers. Eventually, however, 96 of the 126 section supervisors in the Wyoming Division of the Union Pacific were Japanese.

Chikahisa Ota was one of those foremen. Born in in Okayama, Japan, in 1887, he emigrated to the United States in 1907. He worked for Union Pacific in Cheyenne before his promotion to section foreman on the Wamsutter line in Sweetwater County. Ota supervised a crew of mixed nationalities with some success. Sometimes, however, there was interracial tension between the Japanese section laborers and tracklayers of other nationalities—dust ups with Italians and Greeks in Albany and Sweetwater counties among them.

Ota worked as a section foreman until his discharge in 1942 after the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor.

There were Japan Towns in Wyoming.

The Japanese immigrants lived in the principal towns along the UP line– Cheyenne, Laramie, Rawlins, Rock Springs, and Evanston—as well as smaller coal mining communities and some since forgotten places.

Railroad section crews lived in boxcars along the tracks; Japanese coal miners lived in “Jap camps” generally on the outskirts of a community. The section crews worked year around in all weather conditions to keep the UP moving.

Japanese also immigrated into El Paso, Texas to work on the railways.

In the early 1900s, a number of Japanese were entering Texas at the other end of the state. El Paso had long been a border crossing for Chinese immigrants; so much so it had its own “Chinatown.” After Japan’s victory in the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-1905, El Paso became a favored entry point for former Japanese soldiers who were having trouble entering the country at other locations. Many were seeking employment as construction workers for railroad companies, but an agreement between the US and Japan kept such workers out. Unable to enter legally then, an untold number crossed over illegally.

The 1910s saw continued Japanese immigration into Texas through Mexico, largely as a result of unrest caused by the Mexican Revolution. During this period Japanese were also coming to the border areas of Texas from other western states such as California, where they were experiencing considerable discrimination. The Rio Grande Valley area west of Brownsville was a particularly popular destination due to its mild climate and undeveloped, yet fertile, farmland. One migrant to the Valley was Uichi Shimotsu, who settled near McAllen after graduating from a Colorado agricultural college.

The Japanese worked on Mexican mines and railways.

By 1910, Texas had nearly 350 Japanese settlers, and by the outbreak of World War II the number exceeded 450. Many Japanese immigrants entered Texas from the south where they had worked in Mexican mines or on the railroads, and while many of these early arrivals were laborers, some established themselves as businessmen or entrepreneurs.

They were also present in Boulder County, Colorado.

Boulder County enjoys a little-known but rich Japanese legacy. The first Japanese residents in Boulder County moved here as farmers, laborers, miners, and railroad workers. Many literally left their mark on the physical landscape, helping carve Trail Ridge Road from the foot path the Arapaho Indians called the “Dog Trail.” They also blasted rocks from Middle Boulder Creek to build Barker Dam, and burrowed into coal seams in the mines of Erie and Dacono. No job seemed too difficult or dangerous for hard-working Japanese laborers.

Japanese also worked the railways in Nevada.

The San Francisco-based Japan Industrial Association, which provided labor and employment, established a branch in Reno and sent railroad laborers there. Around 1940, there were about 30 to 40 Japanese people living in the Reno area, and there was one Japanese-owned nursery, one hotel, one Western-style restaurant, and one laundry in the city.

Around 1905, over 200 people from the Japan Industrial Association were sent to eastern Nevada to work on the construction of a new railroad in conjunction with the development of the mines. After the development of the Nevada copper mines, Asians were initially unable to work there due to resistance from the labor union, but in 1912, Toyoda Seitaro, a native of Hiroshima Prefecture, sent workers there.

There were a few Japanese railroad workers in Arizona.

Arizona was not a primary destination for most mainland Japanese immigrants, or Issei, who moved east of California for land, jobs, and opportunities. Some came north to Arizona from Mexico. Labor demand for Japanese male workers resulted from the exclusion of Chinese immigrants in 1882, when the Southwest’s need for mine and railroad workers peaked and agriculture emerged as a key industry. In Phoenix, many Issei were agricultural workers; in Williams, they were chiefly railroad workers.

The Japanese residents of Clovis, New Mexico worked the Santa Fe Railroad. Prior to World War II, they lived rent-free in company buildings.

In late January of 1942, 32 Japanese residents of Clovis, New Mexico, were uprooted from their homes and sent to an isolated, little-known confinement camp near Fort Stanton, called the Old Raton Ranch. The Clovis residents included the families of ten Japanese who were employed by the Santa Fe Railroad (primarily as machinists with top seniority), and who had arrived in the town between 1919 and 1922. In 1922 there was a union-led walkout and strike by the railroad shopmen that the Japanese workers refused to join. This contributed to ill feelings on the part of the Anglo workers and in turn, the railroad company favored the Japanese—they had a reputation as excellent workers who caused no trouble. Prior to World War II, the Japanese workers and their families lived rent free in a cluster of one-story buildings that were located 75 yards east of the roundhouse. Although the Japanese were largely isolated, the children attended local schools and some townspeople visited the compound to purchase fresh vegetables and items the families had imported from Japan.

There were Japanese rail workers listed Idaho in the 1900 census, including in Bonner Ferry where the novel and film take place.

The Novella

I was thinking of this after viewing “Train Dreams” because the murder of a Chinese railway worker puzzled me. He was portrayed as being alone which seemed suicidal. The timeline seemed wrong. His murder took place in 1917, meaning post-Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882.

The novella itself only deals with racism in terms of the Chinese and the Native Americans, the Kootenai. After a swift overnight read of the novella, I don’t recall mention of Black/African Americans.

By even polite standards, the racism within the novella “Train Dreams” is slight or mild, but is it as one might expect in a portrayal of a White man during the 1900s to 1960s? That’s long before political correctness and even as of 2025, there seem to be people who didn’t realize that “Chink” was a derogatory term for Chinese or East Asians. The novel begins with the Chinese laborer incident.

In the summer of 1917 Robert Grainier took part in an attempt on the life of a Chinese laborer caught, or anyway accused of, stealing from the company stories of the Spokane International Railway in the Idaho Panhandle.

Three of the railroad gang put the thief under restraint and dragged him up the long bank toward the bridge under construction fifty feet above the Moyea Riber. A rapid singsong streamed from the Chinaman voluminously. He shipped and twisted like a weasel in a sack, lashing backward with his one free fist at the man lugging him by the neck. As this group passed him, Grainier, seeing them in some distress, lent assistance and found himself holding one of the culprit’s bare feet. The man facing him, Mr. Sears, of Spokane International’s management, held the prisoner almost uselessly by the armpit and was the only one of them besides the incomprehensible Chinaman, to take during the hardest part of their labors: “Boys, I’m damned if we ever see the top of this heap!” Then we’re hauling him all the way? was the question Grainier wished to ask, but he thought it better to save his breath for the ask, but he thought it better to save his breath for the struggle. Sears laughed once, his face pale with fatigue and horror. They all went down in the dust and got righted, went down again, the Chinaman speaking in tongues and terrifying the four of them to the point that whatever they may have had in mind at the outset, he was the deader now. Nothing would do but to toss him off the trestle.

They came abreast of the others, a gang of a dozen men pausing in the sun to lean on their tools and wipe at sweat and watch this thing. Grainier held on convulsively to the Chinaman’s horny foot, wondering at himself, and the man with the other foot let loose and sat down gasping in the dirt and got himself kicked in the eye before Grainier took charge of the free-flailing limb. “It was just for fun. For fun,” the man sitting in the dirt said, and to his confederate there he said, “Come on, Jen Toomis, let’s give it up.” “I can’t let loose,” This Mr. Toomis said, “I’m the one’s got him by the neck!” and laughed with a gust of confusion passing across his features. “Well, I’ve got him!” Grainier said, catching both the little domon’s feet tighter in his embrace. “I’ve got the bastard, and I’m your man!”

The party of executioiners got to the midst of the last completed span, sixty feet above the rapids, and made very effortless to toss the Chinaman over. But he bested them by clinging to their arms and legs, weeping his gibberish, until suddenly he let go and grabbed the beam beneath him with one hand. He kicked free of his captors easily, as they were trying to shed themselves of him anyway, and went over the side, gangling over the gorge and making hand-over-hand out over the river on the skeleton form of the next span. Mr. Toomis’s companion rushed over now, balancing on a beam, kicking at the fellow’s fingers. The Chinaman dropped from beam to beam like a circus artist downward along the crosshatch structure. A couple of the work gang cheered his escape, while others, though not quite cetera in why he was being chased, shouted that the villain ought to be stopped. Mr. Sears removed from the holster on his belt a large old four-shot black-powder revolver and took his four, to no effect. By then the Chinaman had vanished.

Grainier went home after the incident to his wife and daughter.

Walking home in the falling dark, Brainier almost met the Chinaman everywhere. Chinaman in the road. Chinaman in the woods. Chinaman walking softly, dangling his hands on arms like ropes. Chinaman dancing up out of the creek like a spiker.

At home, Grainier doesn’t mention this to his wife who is nursing their baby. But later he thinks back to the “Chinaman.”

Now Grainier stood by the table in the single-room cabin and worried. The Chinaman, he was sure, had cursed them powerfully while they dragged him along and any bad thing might come of it. Though astonished now at the frenzy of the afternoon, baffled by the violence, at how it had carried him away like a seed in the win, young Grainier still wished they’d gone ahead and killed that Chinaman before he’d cursed them.

On page 26-27, Grainier recounts the purging of the Chinese from the town when he had just arrived on the train to stay with his uncle and cousins.

His earliest memory was that of standing besides his uncle Robert Grainier, the First, standing no high than then elbow of this smoky-smelling man he’d quickly to calling Father, in the mud street of Fry within sight of the Kootenai Riber, observing the mass deportation of a hundred or more Chinese families from the town. Down at the street’s end, at the Bonner Lumber Company’s railroad yard, men with axes, pistols, and shotguns in their hands stood by saying very little while the strange people clambered onto three flatcars, jabbering like birds and herding their children into the midst of themselves, away from the edges of the open cars. The small-flat-faced men sat on the outside of the three groups, their knees drawn up and their hands locked around their shins, as the train left Fry and headed away to someplace it didn’t occur to Grainier to wonder about until decades later, when he was a grown man and had come very near killing a Chinaman–had wanted to kill him. Most had ended up thirty or so miles west, in Montana, between the towns of Troy and Libby, in a place beside the Kootenai River that came to be called China Basin. By the time Grainier was working on the bridges, the community had dispersed, and only a few lived here and there in the area, and nobody was afraid of them any more.

History

You might think that “China Basin” was named for the Chinese. That’s what the novella leads you to believe. Yet, because the Chinese were the first East Asians in the US, all East Asians became Chinese.

There were other places that seem to have been actually named for nameless Chinese workers such as “Chinaman’s Gulch” in Colorado. That man was gone by 1889.

The role of Chinese immigrants in mining and the building of Colorado railroads is a fact. According to the GBN, a section of the Middle Fork South Platte River near Alma, 33 miles to the north, has been referred to as Chinaman’s Gulch or Chinamen’s Gulch because of the many Chinese miners living there in the 1800s. Chinamans Canyon is located 130 miles to the southeast in Las Animas County.

In Montana, Chinamen’s Campground was named after Chinaman Cove and Chinaman Gulch. “Throughout the 1860s through 1890s there were substantial Chinese populations mining gold, working and living in the area.” If those geographical locations got their names in the 1880s to 1890s, that makes sense, while China Basin got its name in 1918. The incident in the novella and film where men attempt to kill the Chinaman is in 1917.

According to the StumptownHistoricalSociety.org, in Whitefish, Montana, there were at least three minority groups that came to the area early on: Italians, Japanese and Chinese. “The Japanese were accepted earlier and more readily than the other two groups.”

In other areas, the Chinese were being driven out of towns.

- Chinese Massacre of 1871 (Los Angeles)

- War in the Woods (December 1881, Montana)

- Rock Springs Massacre (2 September 1885)

- Pierce City (Idaho Territory) Lynching (18 September 1885)

- Hells Canyon Massacre of 1887 (Oregon near the Idaho border)

While the Chinese were massacred in the 1870s and driven out of towns in the West in the 1880s, Whitefish drove their Chinese out in 1904.

The Chinese, rather than the Japanese, bore the full brunt of Whitefish prejudice. As already mentioned, in January, 1904, all Chinese were being escorted out of town in the direction of Kalispell or Columbia Falls. By October of the same year.

“The Chinks are getting a strong foothold in Whitefish and are making an effort to corral the restaurant business. Ten-Day Jimmy, when he saw a yellow invasion threatened, concluded to change his base. The Caucasians are to blame…Lack of reliable white help in the kitchens is responsible…for the presence of John and his cousins.”

Chinese “noodle joints” were repeatedly described by the Pilot in derogatory style. The Chinese New Year-celebrated for two full weeks in the Chinese settlement-was treated in facetious mood. The Chinese and their eating establishments either were, or were considered to be, often unsanitary, “dirty.” A Whitefish woman remembers being asked. “But would you like to sit on the train next to a Chink?”

In the novella “Train Dreams,” Grainier’s first memories is over the mass deportation of the Chinese families from town. This would have been sometime soon after his arrival in 1893 in Fry, Idaho. I thought the mobs driving the Chinese out were in the 1870s and 1880s. Yet in Whitefish, Montana, that happened in 1904.

I wonder if those Chinese felt they were safe since the wave of massacres and mobs had passed.

Elsewhere I did find another page on Idaho’s Chinese History which noted:

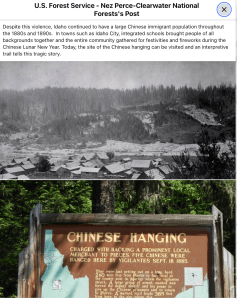

Idaho’s sentiment against Chinese people went as far as an anti-Chinese convention organized in Boise on February 25, 1886. Throughout the 1890s and early 1900s, several towns would follow suit, including Bonners Ferry, Clark Fork, Hoodoo, Moscow, and Twin Falls, forcibly expelling Chinese locals. In 1891, Idaho’s first state legislature enacted a law preventing Chinese immigrants who were not U.S.-born from purchasing or owning property. Sadly, by 1910, Idaho’s once-booming Chinese population had all but disappeared. As Chinese population numbers dwindled, so did the anti-Chinese sentiment. Some Chinese families maintained residence in local communities throughout the 1920s and 1930s in cities like Boise and Lewiston. Still, their presence became less visible as many moved away or left the US altogether. Over time, the overt discrimination and hostility they once faced began to fade.

Another article gave the years for anti-Chinese violence.

Incidents of anti-Chinese violence escalated. Atrocities in Rock Springs, Wyo. (1885), and elsewhere helped lead to the 1887 massacre of at least 34 Chinese miners on the Oregon side of the Snake River, not far from Lewiston. Subsequently, Idaho hooligans ran the Chinese out of Clark Fork (1891), Bonners Ferry (1892) and Moscow (1909). Their numbers had reached a “critical mass,” different for every community, that the majority population no longer tolerated. Communities such as Wallace and Twin Falls barred Chinese residents until much later.

The incident at Bonners Ferry is listed as 1892. According to the Blue Review, large numbers of Japanese men began working on the railroads in early 1892, but it also notes that mid-year 150 Japanese were “run out” of Nampa, Caldwell and Mountain Home. The overt reason was confirmed cases of smallpox. According to the Idaho Statesman, the Japanese consul at San Francisco investigated and “found that those expelled had since returned and were working on the Oregon Short Line, the part of the Union Pacific system that crossed Southern Idaho. That makes it seem as if what happened at Bonners Ferry was related to or perhaps sparked by the influx of other East Asians and this makes more sense. So I wonder if the Chinese resented the influx of Japanese as a result.

According to The Blue Review article, there was concern in Bonners Ferry about the Japanese.

In mid-December 1898, a Bonners Ferry newspaper reported, “A large number of [Japanese] have appeared on our streets this week. … They will … clear right-of-way on the new road [Great Northern].” The editor also commented elsewhere, “If the Japs [sic] continue to pour in, Bonner’s Ferry will appear like an Oriental town, in a short time.” Since only six years had passed since Bonners Ferry had run out the town’s Chinese residents, the editor likely intended his inflammatory statement as a very real threat. Northern Idaho’s Japanese railroad workers continued to appear in unflattering or inflammatory news reports. In early May 1899, “a large force of Japanese laborers” reinforced the railroad bed “to withstand the annual high water.” Not surprisingly, men were occasionally injured or even killed on the job.

“Jap Blown to Atoms,” Kootenai Herald, February 12, 1904, one killed. Unlike news stories about Caucasians, the names of the injured or killed Japanese were seldom given. The last account is an exception; the deceased man was Ringoo Uchida.

But there’s another event at or at least near Bonners Ferry, the Big Burn in the summer of 1910 (also called the Great Fire of 1910). The fire burned about 3 million acres, crossing three states: Idaho, Montana and Washington. While Bonners Ferry wasn’t directly affected, areas near it were. As it turns out “many railroad laborers joined their efforts and fought fires, including Japanese workers.” According to the paper “Pioneers at the Edge of their Universe: Japanese Railroad Workers in Idaho and the Intermountain West,” ten Issei died fighting the fires.

I am doubtful that the anti-East Asian sentiment actually dwindled. More likely the prejudice was latent, easily reawakened by World War II. Idaho was the site of the Minidoka concentration camp. According to Densho:

Relative to other WRA camps, the Minidoka inmates seemed to have more—if not necessarily more cordial—interaction with surrounding communities, which included sixteen towns with a total population of 36,000 within twenty-five miles of the camp. The largest of these towns was Twin Falls, with a population of 12,000. Local sentiment was influenced by Governor Chase Clark’s strident anti-Japanese stance—he claimed that “Japs live like rats, breed like rats, and act like rats” while trying to prevent Japanese Americans from settling in the Idaho—and the Japanese capture of 1,000 Idahoans working for Morrison Knudson in the Pacific. By the time inmates started to arrive at Minidoka in September 1942, Japanese Americans released from assembly centers to work in nearby sugar beet fields—and patronize local businesses—may have started to change at least some local opinions. [19]

By the fall of 1942 Minidoka inmates had begun to have significant interactions with the local communities. Due to the ongoing labor shortage on western farms, Japanese American inmate labor was highly sought after, and some 2,300 Minidokans left the camp that fall to do farm work, much of it in Idaho, to generally favorable local notices. Sub-groups of those out doing farm work also visited local communities. The Harmonaires, a dance band whose members were among those doing farm work, played local dances, while others played basketball against local teams or sang in churches. A Minidoka choir directed by Seattle Methodist Church Choir Director Iwao Hara also toured nearby churches drawing large and enthusiastic crowds. At the same time, Minidoka inmates were allowed to go into Twin Falls in substantial numbers where they patronized the local businesses. In his diary, Kamekichi Tokita wrote that due to the “money Japanese people spend in Twin Falls,” that “Japanese people’s popularity has done a complete turnaround.” [20]

Still reaction continued to be mixed. In May of 1943, the Twin Falls Kiwanis Club adopted a resolution condemning the speaking of foreign languages on the streets and in stores, a measure clearly aimed at Minidoka inmates who patronized local businesses. Later that year, Twin Falls residents complained that Minidokans were “buying up a large proportion of the small liquor supply made available to the public at the State Liquor Store in Twin Falls.” On the other hand, the well-publicized exploits of the Nisei soldiers of the 442nd Regimental Combat Team helped influence public opinion in a positive direction. [21]

Where did the Chinese go after they were driven out of Bonners Ferry? In the novella, “Most had ended up thirty or so miles west, in Montana, between the towns of Troy and Libby, in a place beside the Kootenai River that came to be called China Basin.” Montana had several historic Chinatowns in Butte, Helena, Big Timber and mining towns like Granite. In 1870, the Chinese were 20% of the Deer Lodge County.

There were Chinatowns in Idaho such as in Boise and the mining town of Hailey. Even in the Chinatowns, they were not treated well.

Discrimination was embedded not only in newspaper propaganda, but daily life. Hailey residents held “snowballing parties” on Main Street after snowstorms, for example—a pastime that involved hitting as many Chinese men with snowballs as possible.

“This was a bad day for Chinamen, and any one of them unlucky enough to come across one of the snowballing parties on Main Street, has cause to remember the occasion,” Picotte reported after one snowstorm in February 1884. “This is probably reprehensible; but, then, the snow balled so easily that the temptation to throw was irresistible.”

There’s less detail about possibly negative treatment of the Japanese immigrants. During the Russo-Japanese War (1904-1905), the town of Whitefish was supportive of Japan.

When young Japanese in Whitefish returned to Japan to fight for their country, they were seen off with celebration by the entire town. When Japanese diplomats, led by Baron Komura, went through on their Great Northern trip from Tokyo to Washington during the war they were given a celebration at the depot that included Japanese flags and emblems, fireworks, the Kalispell band, a large crowd of both Japanese and whites. Baron Okado and President Theodore Roosevelt later stopped at Whitefish during peace negotiations, and were given an enthusiastic welcome. The Baron would not get out of bed, but “Teddy” came out on the platform in a nightshirt and overcoat, made a friendly little talk, and was wildly cheered

The town had successful businessmen.

In the early years Japanese managers for the Oriental Trading Company were enterprising and respected. And then M. M. (“Swede”) Hori, who had been a houseboy for the Conrad family, Kalispell financiers, was given ten acres of Whitefish land by his employer and moved to Whitefish. He opened the Hori Café and Hotel, and in 1919 turned it into a $50,000 building extending from the present Pastime to the Toggery. It was the most popular eating place in town, and in the lobby of the hotel were renowned heads of elk, buffalo, and deer, prepared by the local taxidermy. Hori operated this business until his death in 1931, and Mrs. Hori continued its operation fifteen years longer. During her ownership Mrs. Hori, who had come to Seattle from Japan in 1911 and married Hori in 1915, is said to have fed all transients who came to her. Some chopped wood in return, but she fed everybody regardless of payment. Her dairy and truck farm were operated for her by the Sakahara family while she ran the café.

That was Montana, but Idaho was different, according to the Idaho Statesman.

In Mountain Home in January 1898, eight masked men chased a crew of Japanese section hands 2 miles out of town. The Japanese returned later and were placed under the protection of the Elmore County sheriff. The 1898 Legislature passed an anti-alien labor law forbidding the employment of aliens by corporations in the state of Idaho, aimed directly at Japanese railroad workers. In August 1899, the Mountain Home Bulletin reported that Pat M. Sullivan, section foreman of the Idaho Short Line at King Hill, had been arrested and charged with violating the law. “The trial resulted in a conviction, the offense being a misdemeanor. An appeal was filed and the case will be taken to the district court and the fight will be made on the constitutionality of the act. This is the first trial under the anti-alien law in this state, and it will be doubtless carried to the Idaho Supreme Court. The issue involved in this suit is important to the labor element, as it will decide whether or not American laborers can be displaced by Asiatic coolies or European contract slaves. The prompt manner in which the case has been handled shows that Elmore County has officers who are not swayed by corporate influence and do not falter in line of duty.”

The United States Census for 1900 listed 53 Japanese railroad workers in Bonners Ferry with the year they arrived in America — the earliest was one man who came in 1890; 30 came in 1900. Other Idaho towns with Japanese listed in the census as “railroad worker” were Post Falls, 16; Naples, 10; Priest River, 15; Cocolalla, 14; Harrison, 6; Bliss, 12; Mission, 20; Rexburg, 11; St. Anthony, 11; Rathdrum, 4, listed as “prisoner and railroad worker.” (There is surely a story there.) Sandpoint had 99 Japanese at work on the Great Northern Railway. Only Boise had more with 200, 136 of whom had arrived in 1900.

There were states where no anti-miscegenation laws were passed. Idaho, Montana and Oregon were not one of those. In Idaho, anti-miscegenation laws were passed in 1864 targeting Blacks and Asians. The laws were repealed in 1959. That would be before Loving v. Virginia (1967) but after Perez v. Sharp (1948). Oregon had miscegenation laws from 1862 prohibiting marriage between White people and Blacks, Native Americans, Asians and Native Hawaiians. The laws were repealed in 1951. Both Idaho and Oregon had these miscegenation laws before the end of the American Civil War (12 April 1861 – 26 May 1865) and before Chinese Exclusion Act. Montana waited until 1909 to place anti-miscegenation laws on the books (Blacks and Asians). The law was repealed in 1953. Montana waited until after the Chinese Exclusion Act (1882) and just before the US-Japan Gentlemen’s Agreement (1907-1908). Japanese and other South and East Asian immigration would be further limited by the Johnson-Reed Act of 1924.

The Film

The film tones down Grainier’s possibly racist thoughts at the nameless Chinese man. He’s not called a “weasel” or a “demon” and he doesn’t have “horny” feet. In the book and the film, the man is never called a “Chink.” And yet, in the novella, the Chinaman escapes where in the film, he is defeated by the White men and thrown to his death. Instead of a living threat, he becomes a ghost.

The treatment of the Chinaman, who in the film is given the name Fu Sheng (Alfred Hsing), is contrasted by the gang of White loggers being confronted by a Black man. The Black man, Elijah Brown (Brandon Lindsay), shoots a White man, Apostle Frank (Paul Schneider). Yet no one moves and there seems to have been no lynching party formed.

According to the NAACP, Idaho recorded zero lynchings, but likely they only mean of Black persons between 1882 to 1968, but that wasn’t true for the Chinese in Pierce City (Idaho Territory) where in September 1885, five Chinese men were lynched.

According to the NAACP, Idaho recorded zero lynchings, but likely they only mean of Black persons between 1882 to 1968, but that wasn’t true for the Chinese in Pierce City (Idaho Territory) where in September 1885, five Chinese men were lynched.

While the lynchings of Chinese such as the Los Angeles massacre and the War of the Woods are outside of the NAACP dates, the Pierce city incident is not.

There is no mention of the Black man Elijah Brown, who comes from New Mexico to avenge his brother’s death in the book unless I missed it from reading too quickly. In the film, that incident seems added to contrast and remind us of why the Chinaman was killed, because of the color of his skin. Unfortunately, the film’s portrayal reinforces a contemporary narrative of helpless East Asian man but virile and assertive Black man (e.g. the secret casino scene in “Black Panther”).

There seems no reason to include a Black man in the film’s narrative as currently Idaho is 83% White with a 13% population of Hispanic/Latino population. Asian is 1.32% while Black or African American is about 0.75% (although granted the Black man in the film is from out-of-state). It might have been better to amplify the Native Americans. There is a Native American character, but the presence of Native Americans in the book looms larger and there’s some slightly misogynistic thoughts as well.

Conclusions

While I can’t say for sure, it would seem more likely that the Chinaman (known in the film as Fu Sheng) was Japanese because of the year, 1917. Further, the possibility of there being no differentiation between Japanese and Chinese seems increased by the casual assumption the reader is led to in the passage about China Basin.

In 1910, the Japanese population in Idaho was 1,363 and this source has the 1920 Japanese population at 1550. The Japanese population in Idaho was 1,569 in 1920 according to another source (DiscoverNikkei.org) although it decreased to 1,191 in 1940.

By contrast, the Chinese population in Idaho was only 859 in 1910. In Boise, fewer than 600 remained by 1920. Boise is 445 miles from Bonners Ferry. According to the Idaho Statesman, by 1940, the Chinese population was only 208.

With no mention of the ensuing wave of Japanese railway workers, there is an erasure of Asian American history that could have been echoed when Idaho has a Japanese American concentration camp. Minidoka, and the governor has a decidedly anti-Japanese opinion. World War II and its effect on Idaho is totally skipped. Granted Minidoka, Idaho is about 400 miles away from Bonners Ferry, and Grainier wasn’t concerned much with the outside world after the death of his wife and child. Still, the attempt to make our protagonist more acceptable by downplaying racism toward Chinese is troubling because doesn’t it also erase the racism that people of East Asian descent faced in Idaho?

In a sense, both the novella and the film make Grainier less a man of his time by downplaying the racism that was acceptable around 1917 to 1960. The protagonist dies in 1968 (November), after the passing of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

I am glad that I decided to explore the history of Japanese immigrants and the railways because I learned that Japanese immigrants worked on the railways far beyond California. I also became aware of their involvement in mining.

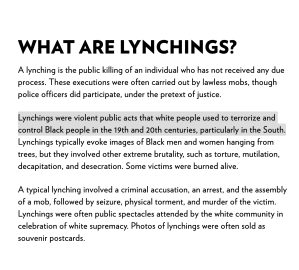

Lastly, I noted that the NAACP website isn’t a good source about the US history of lynching. It claims there were no recorded lynchings in Idaho, when obviously there was, but the whole article is really about Black people and lynchings involving Black people.

NB:

This is not really the “History of Lynching in America.”

The NAACP gives a narrow definition of lynchings. “Lynchings were violent public acts that white people used to terrorize and control Black people in the 19th and 20th centuries, particularly in the South.” This is only about Black people.

I did quick searches for Arizona, Maine, Nevada, South Dakota, Vermont and Wisconsin for Asian and Mexican lynchings.

A Mexican man, Louis Ortiz, was lynched by a mob in Reno, Nevada, in September of 1891.