As a theater critic, I’m familiar with “Hedda Gabler,” the play that the film “Hedda” is based on. Despite my love for the 1950s fashion and the series “Downton Abbey,” I questioned why a US-born filmmaker Nia DaCosta would take a US-born actress (Tessa Thompson) as the lead and then transport the action to Great Britain in the 1950s?

Of course, 1950s in the US wasn’t a great time for African Americans, although the issue of race wasn’t as pronounced in some places. How do we get an African American in England? In this case, Hedda Gabler (Thompson) is married to George Tesman (British actor Tom Bateman) and Tesman is British. One of Hedda’s frenemies, Judge Roland Brack (British actor Nicholas Pinnock) is also Black and British.

DaCosta studied in the UK for her master’s degree and this is when she first thought about adapting “Hedda Gabler.”

Hedda Gabler

If you’re not familiar with this source, the play “Hedda Gabler” had its world premiere in Munich, 31 January 1891. The playwright, Henrik Ibsen (20 March 1828 – 23 May 1906), is sometimes called the father of modern drama because he pushed theatrical realism. He was not part of the aristocracy, but from a merchant family. Born in Norway, he lived in Italy and Germany for 27 years.

You might want to find a more traditional production of this play and I found two and streamed one.

Hedda Gabler (1981) ⭐️⭐️⭐️

Currently, the 1981 version of “Hedda Gabler” is available to stream. I could not find 1962 with Ingrid Bergman or the 1975 film, “Hedda,” with Glenda Jackson. Under the direction of Trevor Nunn, Jackson was nominated for a Best Actress Oscar and she was also nominated for a Golden Globe and the film was nominated for Best Foreign Film (This was before the Golden Globe category was changed to Best Foreign Language Film).

Currently, the 1981 version of “Hedda Gabler” is available to stream. I could not find 1962 with Ingrid Bergman or the 1975 film, “Hedda,” with Glenda Jackson. Under the direction of Trevor Nunn, Jackson was nominated for a Best Actress Oscar and she was also nominated for a Golden Globe and the film was nominated for Best Foreign Film (This was before the Golden Globe category was changed to Best Foreign Language Film).

In the 1981 version, Diana Rigg stars in the title role. Rigg’s Hedda wears dresses that don’t even border on risqué. Her gowns cover her neck and limbs. Her problem isn’t her unbridled sexuality and her body isn’t her weapon of choice. Instead we focus on her angry beauty. She is married to a an adoring balding scholar, George Tesman (Dennis Lill who had previously played the Prince of Wales, Bertie, in the miniseries “Lillie” in 1978).

Her old lover has, Eilert Løvborg (Philip Bond), with the help of a married woman, Thea Elvstead (Elizabeth Bell), sobered up and now has written a book which is now the toast of the town. While Hedda believes this is a threat to her husband’s promotion at the university, Eilert denies interest in the position. Still, when her husband finds the manuscript, the only copy of his followup book which Eilert has accidentally dropped, Hedda burns it to protect her husband. The loss of the manuscript sends Eilert back into an alcoholic haze, too ashamed to admit to Thea that he has lost “their child.”

Hedda gives Eilert one of her father’s guns and tells him how he should commit a beautiful departure. The judge brings news of Eilert, not telling Thea the truth, but telling Hedda that he knows her role in Eilert’s death and now she’s under his control.

When she learns that Eilert failed to die nobly, and her husband George begins to work with Thea to re-construct the manuscript that Hedda has burned, Hedda decides to commit suicide with her father’s gun.

Rigg’s Hedda is a strong woman with a backbone of steel and a resolution of a general. Her Hedda absolutely adhere’s to her father’s military legacy and the suicide, while still shocking as a woman’s choice, is the logical conclusion for her. This is a thrifty version directed by David Cunliffe (18 April 1935 – 1 January 2022) for TV and comes in at only 1 hour and 18 minutes. “Hedda” (2025) runs 1 hour and 47 minutes.

Hedda (2025) ⭐️⭐️⭐️

The film begins at the end. Hedda (Tessa Thompson) is being questioned by law enforcement. They ask her to start at the beginning, but one imagines, she’s not telling them everything, but taking the audience in a flashback of her memory.

Hedda walks into the cold water of the lake that borders the estate that she and her husband, George Tesman (Tom Bateman) are renting. We’ll learn that they can barely afford it. Much of the money came from Judge Roland Brack (Nicholas Pinnock).

George spent a considerable amount of money on their honeymoon where he did research and Hedda realized how bored she already was. Even though there’s a party coming up, she walks into the cold water and then stops when she hears voices calling her.

Her lover, Eileen Lovbord (Nina Hoss) will be attending her party. The party is supposedly put on as part of her husband’s campaign for a professorship. Professor Greenwood (Finbar Lynch) has the power to decide whether the position goes to George or not.

Hedda decides to manipulate the situation to get revenge on her former lover for calling Hedda a coward for settling into a heterosexual life with a particularly boring though intelligent man and perhaps for her lover doing better without her. Isn’t the best revenge living well? Hedda also meets Eileen’s current lover, Thea Clifton (Imogen Poots), whom she considered inferior in so many ways.

Instead of trying to honestly improve her husband’s position, Hedda works to manipulate her guests. It is Hedda and not George who finds the manuscript, but Hedda later burns it. George attempts to stop her, but Hedda convinces him that this will help them.

In the background, the Judge has been observing Hedda and her scheming.

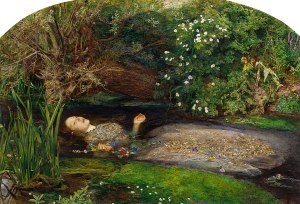

Hedda has been playing dangerous games and she has been caught. She doesn’t decide to commit a stereotypically woman’s suicide in the play. Yet here, the script compromises. Hedda is not going to be an ugly corpse. She will drown herself and be left unmarred like Hamlet’s Ophelia. Her face and dress will be intact. Watching these scenes, I immediately thought of John Everett Millais’ “Ophelia.”

Hedda has been disappointed with the lack of romance and drama in the apparent death of her former lover. Perhaps she wants people to think she drowned accidentally while she was “searching” for the lost manuscript. Even here, the script hesitates and turns away from a brutal finality. All that has gone before is twice betrayed by this determination to leave open the possibilities of the two main female characters continuing on, forced to soldier on to face their ruined lives.

In the play and the 1981 version, Hedda’s husband has risen to be a more noble character, hoping to salvage something to help his rival’s reputation in the future, feeling somewhat guilty for his relatively innocent part. He simply hesitated, waiting for the next day to return the manuscript. He will be one of the keepers of the posthumous honors along with the lover. Hedda isn’t wanted or needed here. In this 2025 film, George doesn’t find the manuscript; he just doesn’t prevent Hedda from burning it up. His responsibility is lessened while Hedda’s is increased.

In the play and in both films, Hedda’s husband is turning away from her. When the play ends, we are left thinking about the different possible reactions of her husband, the judge and her rival Thea upon discovering Hedda’s death.

In the 2025 film, however, we are left wondering what Hedda has decided and how George will doubtlessly suffer for his love. The title of the original play ties Hedda to her father instead of her husband. This 2025 film explains that she is illegitimate, but her careless use of the guns at the beginning doesn’t tie into the ending nor give this Hedda a solid, uncompromising connection to the unseen general who was her father. His presence doesn’t loom over this version of Hedda nor doom her.

I was further distracted by Hedda’s dress because I wondered if such a design would have been possible in the 1950s without the current types of fabrics we use, but I’ve also just binge watched “The Great British Sewing Bee.”

I was further distracted by Hedda’s dress because I wondered if such a design would have been possible in the 1950s without the current types of fabrics we use, but I’ve also just binge watched “The Great British Sewing Bee.”

There were other problems of contemporary technology that bothered me. While in the time that Ibsen wrote, typewriters and carbon paper were rare with the first typewriter patent issued in 1714 but the first successfully marketed machine developed by US inventor Christopher Latham Scholes in 1868, by the 1890s, there were British manufacturers. By the 1950s, manual typewriters were common place in offices. Electric typewriters were first produced in the 1930s and gained wider acceptance in the 1950s.

Carbon paper was created in 1801 in Italy and then a form was patented in England in 1806. By the 1950s, improvements were made to the coating, but the rise of photocopiers and computer printers made these mostly obsolete. Yet photocopiers were something that became more prominent in the 1960s. In the 1950s, there were mimeographs. The mimeograph was being used to print newsletters and little magazines by the 1940s. This article from National Geographic shows a photo of British soldiers using a mimeograph machine to make news sheets.

The existence of carbon paper and typewriters and mimeographs in the 1950s, changes how one views the writer who is Hedda’s former lover. Where one would not expect there to be any precautions or copies in the original time period, in the 1950s, failure to make a copy makes the writer seem careless or even reckless.

The lesbian angle is intriguing and makes Hedda more sympathetic as a woman hiding in the closet, but I didn’t find her friends appealing. They are those sloppy drunk party people sensible people avoid. Would those people really help George shine in the eyes of Greenwood? I would think they would be more damaging by association.

Moreover, Hedda isn’t very likable as we see her trying to destroy others, from her husband to the one living person she supposedly loved, Eileen Is this all self-hate due to repressed lesbianism?

Yet, for me, in the end, it is not the lesbian-angle that lets this tale down and makes it tame as opposed to shocking. It is the resolution that deviates greatly from the original. There’s no bang that even when I know it’s coming, it still makes me tense up. Hedda isn’t her father’s daughter and she is instead the villainous who will destroy George’s happiness while attempting to break free from the judge’s hold over her.

It’s as if once creating this Hedda, DaCosta was loathe to destroy her through death and that’s a shame. Under DaCosta’s direction, Thompson is mesmerizing as the unhappy temptress and master manipulator. Her Hedda’s dealings with Pinnock’s slithery judge are nuanced with hints of danger that almost become a frightening rape reality.

See “Hedda” for the performances and the beautiful cinematography, but remember this strays from the original ending. I saw Annette Bening in “Hedda Gabler” at the Geffen Playhouse in 1999. And that was a richer experience.

“Hedda” made its world premiere at the 2025 Toronto International Film Festival in September. It was released in the US in October and is currently streaming on Amazon Prime Video.