In the US, the word “Asian” is probably more closely associated with things “East Asian” while in places like the UK, it’s more likely to reference things “South Asian.” Of course, there is a world of difference between China, Japan and South Korea compared to India and Pakistan, but remember that Asia is a continent that includes the Middle East. Once upon a time, the word “Oriental” included the Middle East, the Near East, South Asia on to the Pacific Islands.

While Merriam-Webster defines Oriental as “of, relating to, or constituting the biogeographic region that includes Asia south and southeast of the Himalayas and the Malay Archipelago west of Wallace’s line” or “relating to, or coming from Asia and especially eastern Asia,” it also notes, “The noun Oriental has a long history of association with colonialism and with language that others and exoticizes people of various Asian identities. While Oriental is not offensive in senses 2 and 3 above, the use of Oriental to refer to a person is usually considered offensive.”

This really doesn’t touch fully on why the term “Oriental” is now offensive. It was once a sweeping generalization in the othering of peoples. Present day proof of how broad the term “Oriental” once was is shown in some recent official name changes. In 2022, the University of Oxford announced the Faculty of Oriental Studies was changing its name to the Faculty of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies. In 2023, the Oriental Institute at the University of Chicago changed its name to the Institute for the Study of Ancient Cultures, West Asia and North Africa.

The term “Orient” was the othering of North Africa and Asia. For his 1975 book, “Orientalism,” the Palestinian American scholar Edward W. Said focused on the Middle East and views of Arab culture. And it is the Arab culture that “Dune” raids.

“Dune: Part Two” is a beautifully shot and scripted Lawrence of Arabia in space saga, but in 2024, do we really need the White man saves the desert people movie? The first film left lingering questions, but “Part Two” slides down the slippery slope and sinks in White savior quicksand.

The 1962 “Lawrence of Arabia” was based on T.E. Lawrence’s 1926 book “Seven Pillars of Wisdom” and director David Lean won an Oscar. The film was nominated for ten Academy Awards and walked away with seven. Peter O’Toole played Lawrence, but Alec Guinness played the Iraqi King Faisal, Mexican-born Anthony Quinn played the Bedouin Arab Auda Abu Tayi, José Ferrer was the Turkish Bey and Egyptian-born Omar Sharif was Sherif Ali ibn el Kharish.

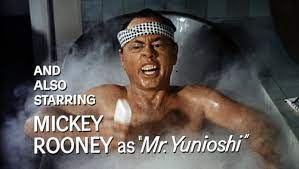

This was only a year after Audrey Hepburn starred in “Breakfast at Tiffany’s” and Mickey Rooney played a buffoonish Japanese man.

“Dune” was published in 1965, written by Frank Herbert. In some ways, it was also a product of the 1960s. Yet that doesn’t necessarily mean Herbert’s view of Islam was negative.

The success of the original novel spawned two separate serials, but the film “Dune” in 2021 (scripted by Jon Spats and Eric Roth with director Denis Villeneuve) only covers part of the 1965 novel that “Dune: Part Two” (written by Spats and Villeneuve) completes.

The story centers on Paul (Timothée Chalamet), the son of Duke Leto Atreides (Oscar Isaac) of the House Atreides by his concubine Lady Jessica (Rebecca Ferguson); we meet all three in the first film. Jessica is an acolyte of a sinister sisterhood, bred to have heightened mental abilities. The Bene Gesserit sisterhood infiltrate the political realm controlled by men via sexual conquest. The Bene Gesserit have a plan and Paul wasn’t part of it. Jessica was supposed to bear the Duke a daughter, not a son. Yet out of her love for the Duke, she had a son. Paul has been trained in warfare by men like Duncan Idaho (Jason Momoa) and Gurney Halleck (Josh Brolin) because the worlds ruled by the Emperor are filled with death. Leto has been ordered to leave the wet planet of Caladan for the desert planet of Arrakis. He is replacing the House of Harkonnen. Arrakis is the sole place where the “spice” can be found and harvested. It is a necessary substance for interstellar travel, but also something that has a desirable effect on humans who consume it.

The House Harkonnen–Baron Vladimir (Stellan Skargård) and his nephew Glossu Rabban (Dave Bautista)–is actually conspiring with the Emperor to destroy all of the House Atreides. This betrayal sends Paul and Jessica out of the safety of the fortress and into the realm of giant sandworms and the hostile indigenous Fremen people. Paul has already been tested by the Bene Gesserit Reverend Mother (Charlotte Rampling) and shown to have certain natural abilities usually found only in the sisterhood and Jessica has been training him to use them.

The Bene Gesserit have also been laying the foundation for the rise of a false religion centered on a Messiah.

In “Part Two,” Paul and Jessica have found shelter with the Fremen. Paul has found a cautious ally and lover with the Fremen woman, Chani (Zendaya), and a faithful believer in the Stilgar (Javier Bardem), leader of the Fremen Sietch Tabr. Jessica is pregnant and already can communicate with her unborn child. She becomes more entrenched in the Fremen religion and urges Paul to embrace a messianic mission.

The House Harkonnen brings in the psychopathic younger brother of Glossu, Feld-Rautha (Austin Butler), to replace a failing Glossu Rabban. And the emperor’s (Christopher Walken) daughter, Princess Irulan (Florence Pugh) comes into play.

At the end of the first part, I had questions, but I was hopeful. “Part Two” makes this clearly a White savior film and further builds up the religious beliefs of this Muslim Arab-esque peoples on the desert planet of Arrakis as a product of centuries of planning by a sisterhood led by a White woman (although there are minorities present). Early on, the press screening audience laughed at precisely the moment that I, as a non-Christian, felt uncomfortable.

After viewing “Part Two,” I did some online searches and soon learned that for the first film, there had already been objections over the usage of North African and West Asian traditions (cultural appropriation) as well as accusations of erasure because none of the main characters who are members of the indigenous tribe (Fremen) are of North African origin.

- ‘Dune’ appropriates Islamic, Middle Eastern tropes without real inclusion, critics say “It’s like … our homes and foods and songs and languages are just right for Western stories, but we humans are never enough to be in them,” one critic said. (29 October 2021)

- The novel ‘Dune’ had deep Islamic influences. The movie erases them. The resulting film is both more orientalist and less daring than its source material. (28 October 2021)

- Frank Herbert’s Dune novels were heavily influenced by Middle Eastern, Islamic cultures, says scholar. While set thousands of years in the future, Islam is ‘part and parcel’ to Dune, says Ali Karjoo-Ravary (22 October 2021)

What does this have to do with Asian Americans? Islam is the largest religion in Asia (the second largest is Hinduism). Granted, this includes West Asia, however, consider that in South Asia (Afghanistan, Pakistan, India, Nepal, Bangladesh, Bhutan, Sri Lanka and the Maldives), Muslim make up about a third of the population. In South East- East Asia, Muslims are about 12 percent, yet they are 2 percent of the population of China, “but because the country is so populous, its Muslim population is expected to be the 19th largest in the world in 2030. ”

Pakistan is projected to surpass Indonesia at the country with the single largest Muslim population in the world by 2030.

In the U.S., according to the Pew Research Institute while Muslims only make up 6% of the Asian American population (excluding West Asians), 60% of South Asians in the United States other than Indians Americans are Muslim. While Christianity is the largest faith group among Asian Americans, that’s only 32%, split almost evenly between Catholics and Protestants.

Unlike the many forms of Christianity, Islam has been demonized in the US, and like Hinduism and Buddhism, has been proclaimed a false religion in the US. Islam still struggles for respect, and in the US, certain religions of Asia cannot easily display their symbols (e.g. swastika). “Part Two” builds an uneasy association between a false religion and Islam.

There’s no real sign that “Part Two” in any way has reacted to ameliorate claims of cultural appropriation or erasure although I noticed some Muslim-seeming names in the actors who played warriors loyal to Paul (Fedaykin) and the Fundamentalist fighters. Here, in “Dune” and “Dune: Part Two,” the diversity casting makes this 2024 interpretation more troubling than the predominately White casting of the 1984 David Lynch film. We have Chalamet and Ferguson representing Atreides and Butler, Skargård and a heavily literally whitened Bautista for Harkonnen, and Ferguson and Rampling for the Bene Gesserit, but Bardem and Zendaya representing the Fremen. Having Baptista in the House Harkonnen doesn’t help when his uncle is Skargård and his younger brother is Austin and he’s visually white.

In some ways, “Dune” and “Dune: Part Two” can contrast the recent release of the Netflix series, “Avatar: The Last Airbender.” The original animated 2005 series was first made into a live-action film in 2010 and the casting of predominately White actors in what seemed to be a predominately East Asian and Inuit universe was problematic, even though the film was directed and written by an Asian Indian American, M. Night Shyamalan, and the original animated series was written by two people who were not of Asian descent: Michael Dante DiMartino and Bryan Konietzko. Like “The Last Airbender,” “Dune” is fantasy world, but still doesn’t representation matter?

Perhaps the point should be that diversity doesn’t necessarily mean casting Black people if it doesn’t make any sense. That was true for the Marvel Cinematic Universe which had Black characters in its interpretation of Thor’s world while Asian or Inuit would have made more sense.

I would hesitate to censor Dune because of its 1960s origin and White savior content, yet the United States sees so little representation of Arab American, Persian American, Turkish American and other Middle East-North African American stories in film and on TV. Foreign films from those areas also receive little exposure, even at the Academy Awards.

Would it be possible to take the Orientalism out of “Dune”? Perhaps, but this film won’t do it. Remember, “Lawrence of Arabia” was essentially an Orientalist version of a moment in Arab history. I can’t help thinking that the casting of Bardem is meant to remind us of Quinn’s casting in the 1962 film. For many, the romance of an Englishman making a difference in Arabia will be the most they know about the history of the Middle East during that time period. Moreover, the serious tone of “Dune” makes it harder to dismiss than the tongue-in-cheek near comic book sensibilities of the Indiana Jones saga which has hopped through those areas, including a memorable moment between a gun and a saber.

What would have happened if there had been more involvement from peoples from North Africa or West Asia in prominent positions? Consider that a non-fantasy TV series based on a 1975 novel written by a White man, Australian-born American James Clavell, that is making an effort to avoid Orientalism. The FX miniseries Shōgun has Japanese American Rachel Kondo (with her husband Justin Marks) credited as the creator. It certainly helps that Japanese actor Hiroyuki Sanada is one of the producers and has been very vocal about bringing authenticity to the series.

Still, Clavell’s novel came out a few years before Said’s “Orientalism.” The miniseries reception in Japan will be interesting to note as well as the fantasies viewers come away with.

The Dune production team doesn’t seem to be trying for cultural appreciation over appropriation. And that makes “Dune: Part Two” seem more like a sinister contemporary emissary of Orientalism. We see the beauty of Islamic architecture and windblown fashions based on West Asian and North African cultures, but do we see them as people on the same level as the Atreides or the Harkonnen? We don’t if they need to believe in a false religion and be led by a person who wouldn’t even marry into their culture. While the film’s Orientalism isn’t aimed at East Asians, Southeast Asians or South Asians, this is a racist legacy that haunts the peoples who were all once historically classified as Orientals.

While peoples of East Asian, Southeast Asian and South Asian descent may be forever foreigners in the US, the people of MENA descent are invisible as a socio-political group. They have no continent to call their own as they are in the minds of most US citizens not African or Asian American. They are also currently counted as White and not differentiated within the US Census as Latinos/Hispanics are, White or not White.

Although “Dune” and “Dune: Part Two” was filmed in the West Asian countries of Jordan (Wadi Rum as the Arrakis desert) and United Arab Emirates (Liwa Oasis, Abu Dhabi as the Arrakis desert), it premiered in Mexico (6 February 2024). Other filming locations include Norway (Stadlandet as Caladan) and Budapest, Hungary (Origo Film Studios).

“Dune” and “Dune: Part Two” seem proof that the problems of racism and prejudice in the US toward Muslims and MENA Americans persist and that racial sensitivity and respect have not yet been extended to them. During a time when the question of Gaza and Israel figures prominently in the news, that’s a truly bad sign.

Asian Americans should be concerned because the countries in Asia have Muslim populations and we were once and to some extent still are under the oppression of Orientalism. Shouldn’t we protest Orientalism in all its forms and as minorities shouldn’t be protest the continued seductive romance of the White Savior, at least until there are as many options with Asian and Asian American saviors being produced within the US film and television industry?